Understanding 12 Bar Blues - A 5 Minute Crash Course

The famous 12 Bar Blues...the soundtrack to every dive-bar jam and the guitar players’ handshake – a universally heard musical phenomenon with more variations than Heinz.

It is often, whether we realise it or not, one of the first things many of us as guitar players learn at the beginning of our journey. Or at least, its elements are in our building block starter pack. Though, because of this, the format and fundamental language of the 12 Bar Blues are often skimmed over as being a primitive nursery rhyme, a necessary evil on a road to heavier things.

In actuality, mastering the understanding of this progression format will make you a better rhythm player, improviser and all round musician. So, whether you’re curious at the beginning of your journey, or feel like you need some 12 Bar revision, let’s turnaround and dive into the inner workings of this brilliant progression.

The 12 Bar Progression

The progression is commonly made up of the first (I), fourth (IV) and fifth (V) intervals of major or minor scale.

Both scales are diatonic and contain seven notes. It’s important to point out here that if we are for example in the key of E Major, our first scale interval will be our root note (E), our fourth scale interval will be the fourth note in the E major scale (A) and our fifth scale interval will be E major scale (B).

If we were using the E minor scale, these fourth (IV) and fifth (V) scale intervals are again going to be used, though, this time they would be the minor chords to match the key signature of A minor.

In short, we are always going to be following a one (I), four (IV), five (V) progression using these scale intervals. We will often see this format presented in Roman numerals:

I, IV, V.

When we apply our note intervals to the key of E major, we can begin to closer see how this may look on a chord chart:

E, A, B

I, IV, V

If we then apply this same reading to E minor scale, we would see:

Em, Am, Bm

I, IV, V

Using Dominant 7 Chords

Blues often takes advantage of this and employs dominant 7 chords within the progression, bringing in the tension of a major 3rd scale interval against the minor 7th scale interval.

This is blend of major and minor is in effect, what makes things sound “Bluesy” and is quintessential to the genre. Why not use this to our advantage also and use dominant 7 chords for our I, IV, and V within the progression as follows:

Now, let’s talk about where the number 12 comes into this. We know it’s called a 12 Bar Blues and it’s for a good and very literal reason. In this progression we have 12 bars.

These are usually in the time signature of 4/4 or 6/8 and here, let’s assume the signature of 4/4.

The top number of the signature is the numerator and tells you how many beats to count and the bottom number of the signature is the denominator, telling you what kind of note to count relative to the beat; e.g. - if the bottom number is 4, you will be counting in quarter notes. Or in short, 4/4 would mean 4 beats per bar and in this case, we have 12 of these measures in this progression.

The progression is typically swung or ‘shuffled’, meaning that instead of interpreting the beats as:

“1, 2, 3, 4”

We would hear and feel them ‘pushed’ with the accents being as follows:

“a 1, a 2, a 3, a 4”

From here, all we have to do is arrange our chords into this 12 bar format. Typically, we would begin the progression on chord one (I) for 4 bars, chord four (IV) for 2 bars, back to chord one (1) for 2 bars, then to chord five (V) for 1 bar, chord four (IV) for 1 bar, back to chord one for 2 bars and ending the last 2 beats of bar 12 on chord five (V). The progression and its length then repeat for the desired length of the track (or jam!).

The Turnaround

Once we head to the fifth chord (V), we have arrived at what is commonly known as the turnaround. The name of this phrase too has a very literal meaning, as we are “turning around” the repeated rhythmic pattern back to the first chord with a familiar melodic variation.

Or put simply, we are creating movement within the progression with the natural musical resolution back to the root chord, our one chord (I). Turnarounds are another quintessential trait of a Blues progression (besides the I, IV, V progression itself) and provide the ability to change up both the harmonic presentation, rhythm parts, as well as being an effective way to end the progression.

Shuffled Rhythm

Now we have all our components, let’s focus on a great way to get started playing this progression and settle nicely into the shuffled rhythm. The best way is to simply take the chord and subdivide the length of some beats to eighth notes and focus on the same pushed feel. For example, try saying this rhythm and strumming it at the same time:

“1 e and a 2 e and a 3 e and a 4 e and a”

In terms of theory, the lengths of the beats/notes become sets of triplets, with the first beat being a quarter note, the second an eighth note and the third another quarter note. It’s also important to note that, when using this verbal formula, we are technically counting 2 bars at a time.

If you’re struggling to get it down as a strumming pattern, simply clap the rhythm out and repeat the verbal formula and you’ll have it down soon enough. This helps to eliminate overthinking the theory and understand this in a more natural way.

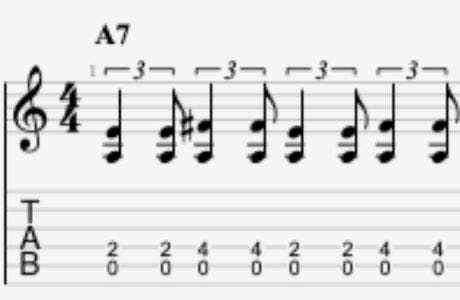

Now let’s look at how we could play this rhythm within each chord over the course of one bar:

Though, when we head to the end of that turnaround it can get a little bit confusing as where to put the final fifth chord (V).

I find, the easiest way to get started with this is to count our triplet verbal formula as it takes up the length of our final two bars and we can play this rhythm over the root chord (E).

However, when we get “3”, we are going to take advantage of our ability to chromatically walk the up the scale intervals to that fifth chord by playing an open A string (IV), first fret A string (the “Blue Note”) and up to the second fret A string.

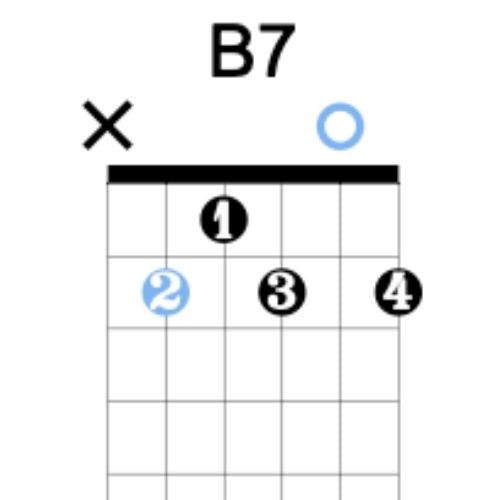

Making 3 a quarter note, we’re going to be playing these notes from 3’s “and a”, reaching the second fret A string on the 4. From here, we can let this B note ring out for the rest of the bar, or alternatively, we could fret a B7 chord for example:

We could then play the “e and a” of our 4 by picked our remaining fretted strings within the chord. Thus, making for a more interesting, more fluid rhythm and retaining the constant driving movement of our shuffled rhythm.

From here, we’re back to repeating the progression with the same chords and rhythmic formulas. Of course, we can put in fills and licks as we gain dominance over the application to help drive the authenticity and make it sound even more “Bluesy.”

Control over the rhythm is often the key with this progression and once we that down, the fun will follow. So practice it, master it and have fun!

Extra-Tip!

Once you have the rhythm down, why not lay the progression down using a loop pedal to start improvising, throwing in your favourite Blues licks and begin mastering the lead side of things.

Or even to see if your fill licks will fit in rhythmically with the foundations you’ve laid down.